Tragic Optimism and other paradoxes

How The Tragic Optimist got his name and how tragic optimism is a philosophy for our “time of monsters.”

Who is The Tragic Optimist and how did he get here? On the first anniversary of this Substack (and another plunge in the freezing Atlantic) let me introduce myself once again. Thanks for tuning in.

“He’s good at titles,” the joke goes, “but best not to read the actual books themselves.” Ha. Whether you share that opinion of my books, I think it’s fair to say, I am good at titles. Titles of books, orgs, projects, concepts, you name it.

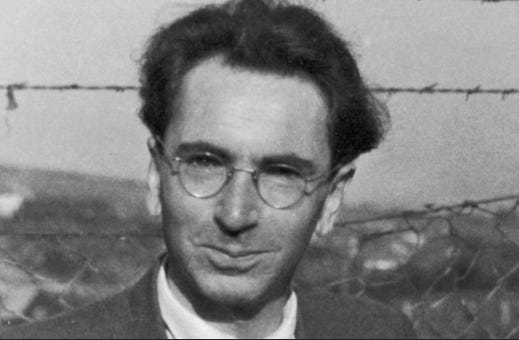

And whether that’s the creative activism of Beautiful Trouble; or the existential self-help of Daily Afflictions; or the climate reckoning of Better Catastrophe; or the academy-hacking of Po Mo To Go and the Philosophical Shit-List; or the faux campaign of Billionaires for Bush; or the pocket philosophies of Skeptical Mysticism, Compassionate Nihilism, Ironic Faith and Can-do Pessimism; or the spiritual questing of Pilgrimage to Nowhere; or the feminism for dudes of Enlightened Machismo; or my preferred form of public performance, Stand-up Tragedy; or the name of this blog — The Tragic Optimist — borrowed from the great Viktor Frankl — there’s always a paradox, or at least an unexpected twinning of opposites, at the core of each.

And of all the hats I’ve worn and alter-egos I’ve tried on — from Captain John Early to Anti-author XL94 to Agent Chartreuse to Phil T. Rich to Mahatma Propagandhi to Brother Void — I’m happy with the one I’m now wearing, The Tragic Optimist, whose essence, “say yes to life in spite of it all,” has been a constant through all of them. If we wanted to trace my several decades-long creative-intellectual journey to see how I’ve landed here, we could do worse than look at this series of hats I’ve worn over the years.

Pocket philosophies

In the very broadest sense, the entire human condition is a paradox. Our lives are temporary and inscrutable, while death is compulsory and forever. (Most great art arises out of this reckoning.) “I can’t go on. I must go on,” say Beckett’s duo as they wait in an empty landscape forever (?) for the mysterious Godot. As an existentially challenged human myself, and especially as an activist trying to stay the course, I’ve had many a battle with meaninglessness and hopelessness, which has led me to devise several paradoxical notions, including Compassionate Nihilism. Here’s how I defined it in the Daily Afflictions’ glossary:

A moral philosophy that permits the subject to love the world in spite of the obvious meaninglessness of all existence. Popular among professional social justice activists who have given up hope but can't think of anything better to do.

Funny ha ha, yes. But it’s really only half a joke. Because it has helped see me through bouts of despair. And not just me: during my AMA on the reddit /collapse thread earlier this year, it was probably the one term that most struck a nerve.

In a similar vein, to address the problem of trying to remain a committed activist amidst the soup of postmodern “truthiness” and ironic detachment, I again reached for paradox, coining the term Ironic Faith, which I describe in Daily Afflictions as, “A philosophical position adopted by those who believe in something but also believe it’s naive and dangerous to believe in anything.” Here is the full spiritual instruction from Daily Afflictions:

Faith and irony

Having said clearly that it is no longer possible to speak innocently, [the ironist] will nonetheless have said what he wanted to say.

—Umberto EcoWe live in an age that has lost faith in itself. It is naive to care, gauche to be sincere and downright suspicious to believe in a better tomorrow. But underneath your cool indifference you probably do care, although you distrust these feelings and you're ashamed to reveal them. Instead, you protect yourself with irony. Irony lets you off the hook and distances you from what you love. But irony also helps you negotiate your faithlessness. When you believe in something but also believe it's foolish to believe in anything, your only honest option is irony. It's how you pay lip service to your nihilism but also vaguely point beyond it.

To have faith today, you must at once affirm your faith and also ironically observe all that makes faith impossible. With one hand you must admit that it's all been done before, that everything is relative, that there's no ground for authenticity, and that every claim to truth is suspect. So that with the other, you can stake your claim with all your heart. In a faithless age, you must lace your faith with irony. It's the only way to take yourself seriously, and the only way to show others that you distrust yourself enough for them to trust you.

+ Irony is the only way I can take myself seriously. +

This general attitude took a more academic form in collaboration with friend and NYU Cultural Studies professor Steve Duncombe in the notion of an “Ethical Spectacle,” which we describe in Steve’s book Dream as, “A propaganda of the truth,” a politics that deploys myth, fantasy and spectacle, but does so knowingly, transparently, and ethically.

My penchant for paradox invention was not limited to the political realm. I was raised atheist, and took to it strongly. Then, in my late teens and early twenties, I had a series of experiences that can best be described as direct cognition of the Divine. (I’ve written about them here, and here and elsewhere.) Did I go off and join a cult? Or abandon rational thought? No. In fact, smack dab in the middle of one of these visions I even tried to apply the scientific method to determine its “veracity.” Yep, I’m a dork. In any case, this all landed me in a profound epistemological crisis. I was still an atheist; I still held fast to a rational, analytic approach to knowledge, and yet, I was having revelations in the William James sense, where a state of knowledge is experienced as a state of feeling. And so, yes, I had to make some quite strange room in my soul to accommodate these contradictory truths, which led me to devise a pocket philosophy for myself called “Skeptical Mysticism.” Here’s how I playfully described it in Daily Afflictions:

A theological stance that permits the subject to hold two divergent epistemologies (a hard-line anti-metaphysical skeptical materialist socio-historical empiricism and an immanent ontological existentialist phenomenology of divine revelation and transcendence) without becoming schizophrenic.

Not sure how helpful this offering is in the battle New Atheism is waging to break religious fundamentalism’s grip over our culture and public policy, but if book tour anecdotes are any tell, it gave my “spiritual but not religious” readers a good laugh as well as some true succor.

Reality is non-binary!

At first blush, this kind of “both, and” approach might feel like a cowardly cop out. As if Pete Seeger is singing Which side are you on, boys…? and you’re trying to stand on both sides of the picket line. But a paradoxical approach is not about staying above the fray, or throwing up your hands and waving the “it’s too complicated” white flag. No, it’s about finding ways to acknowledge, hold, and navigate the inherent complexity of a given situation in order to act more wisely. It’s not motivated by a fascination with complexity for complexity’s sake (as seems all too much the way of the Academy), but rather a commitment to “make things as simple as possible,” as Einstein enjoined us to do, “but no simpler.”

This “but no simpler” part is crucial because, well, reality is complicated, reality is non-binary! Black and white cookie-cutter answers tend to lead to toxic outcomes. Paradox — or at least some comfort with the “messy middle” — is often needed.

The poet John Keats suggested we cultivate the ability of “being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts,” a quality he called “Negative capability.” In Better Catastrophe, I speculated that this approach could be “our wisest response to the impossible era we’re living through,” helping to steady ourselves during our bouts of “apocalypse whiplash” as we try to face the truth of our uncertain future, “when several radically different versions of it are all true-ish.”

In her 1946 treatise Ethics of Ambiguity, Simone De Beauvoir takes to task folks who use “bad faith tactics” to escape the inevitable tension and ambiguity in their lives. Yes, man is both subject and object, both free and “bound by our facticity,” she argues, and yet these ambiguities can’t stop us from acting against oppression to secure our own liberation.

In his 1964 essay In Praise of Inconsistency, Polish Marxist (but anti-Stalinist) philosopher Leszek Kolakowski praises inconsistency as an act of conscience against the totalitarianism and absolutism of both Left and Right. He holds up inconsistency as “a hidden awareness of the contradictions of this world,” and “a continuous awareness that one may well be mistaken or that the enemy may be right.” He claims one can hold multiple “values that are mutually exclusive without [them] ceasing to be values,” and praises the inconsistency of refusing to make an absolute choice between them.

The task of holding contradictory opposites is not just a logical effort to consider all the angles, but an ethical, political and spiritual task as well — an aspect raised to the heights of poetry in James Baldwin’s foundational realization from his 1955 Notes of a Native Son:

It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.

A more compelling — and beautiful — argument for the necessity of paradox would be hard to find.

Living with paradox

So, how exactly do we do this? How do we hold the paradoxes in our world and in our lives? Well, in a word, humility. I’ve found it helps to take a ”be curious, not judgmental” Ted Lasso-esque approach. After all, how many times have I thought I was right (and thought I knew all I needed to know) but I wasn’t and didn’t? How often, wanting a hard answer to land on, have I had to step back into the mystery, the process, the continuing search. “Do not trust those who have found the truth,” Andre Gide tells us, “only those who are seeking the truth.” So, I work at straddling my own messy middle and “staying with the trouble.” And I’m especially wary when I notice myself wanting to feel the one “correct” way about important things.

“A person is a crowded place,” my good friend Michael Barrish used to say. Crowded in ways we are sometimes amazed by, ashamed of, or terrified to acknowledge. Grief, for example, is no orderly 5-stage process. Rather, grief, as each of us learns in time, is a wet, tangled mess that everyone goes through in their own twisted way. My brother died of a drug overdose at 32. After getting the call from the police — and then, in the worst moment of my life, having to tell my parents the bad news — I needed to walk to the precinct to confirm his identity. I was in shock. The air, the streets, felt eerie and surreal; I was an empty shell of myself. But also welling up inside me — unbidden — was this triumphant feeling that I had finally won the mythic Cain v. Abel battle for our parents’ affections. Was I mortified by my own self? Yes. And yet there it was, undeniably happening in my mysterious psyche. The morning the Towers went down, along with my shock and sadness and anger, I was also thinking Gosh, I bet every other terrorist in the world is so bummed out — they’ve been one-upped forever! The second tower hadn’t even fallen yet, the “time” in the “tragedy plus time” equation hadn’t even begun to count down, and already the “imp of my perverse” was monkeying about.

And if we can so surprise ourselves about ourselves, imagine how surprised we would be to learn of the many worlds aswirl in other people souls if we only knew their full stories. Extrapolating from there out to the wider world and to our riven politics, maybe we gain some humility and begin to see how seemingly opposite things can both be true at the same time.

Yes, many good people voted for Trump. Yes, you can like craft beer AND also hate gentrification. Yes, you can be both a pessimist and an optimist, in fact we must be both. ”Pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will!” Antonio Gramsci famously commands us. And look at all the psychic space that opens up when we think of optimism and pessimism not as personality traits or binary ideologies, but as tools, lenses, perspectives that we can pick up to help us see in differently true ways.

Tools can help

Holding these kinds of contradictions is not easy. And so over the years I’ve sought out — and invented — tools to help us out.

All of us have faced never-ending controversies (think: change the world or change yourself?) that must be constantly wrestled with. So, when we created the Beautiful Trouble card deck, we included Eternal Debates, pairs of cards aimed at turning debilitating ideological conflict into a collaborative strategy design process. As an activist, there’s no shortage of false binaries to grow out of, and toxic ones to trip you up on your path. Skillful navigation of contradictions is required. Here are three of the seven Eternal Debates we identified:

Just Do It! -vs- More Theory Needed;

Be the Change You Want to See -vs- By Any Means Necessary;

Class Politics -vs- Identity Politics

These debates are less “winnable” ideological battles, and more design questions with context-dependent trade-offs. You can try them out here. Paradoxes for the win!

Vent Diagrams are a tool developed by Rachel Schragis and Elana Eisen-Markowitz to visualize the tension between two opposing but equally true truths. “Making vent diagrams,” they say, “helps us recognize and reckon with contradictions and keep imagining and acting from the intersections and overlaps. Venting is [...] an emotional release of stale binary thinking in order to open up a trickle of fresh ideas.”

So what happens when we try to apply these tools where it really matters?

In approaching Israel-Palestine, might the paradoxical recognition that a People can be both victim *and* perpetrator open up space for understanding in this most intractable of conflicts? I wrote about this in my own little way post-Oct 7 here on Substack; Naomi Klein, Peter Beinart, Micah Sifry and many others have made far more heroic efforts to do so here and here and here.

Or, take, for example, the war on trans people right now. Might it be possible to take up the fight to protect trans people against the MAGA haters hating on them as the good v. evil fight that it truly is, *while at the same time* treating the issue of, say, how best to include trans-women in female sports as the good v. good conundrum — the good of inclusion vs. the good of fairness — that it truly is? Can we fiercely wage that first fight at the same time that we compassionately have that second discussion?

Or take the so-called “crisis of masculinity.” I’ve long felt that approaches to it have been plagued by false binaries. Under the aspirational notion of “Enlightened Machismo,” I’ve been arguing for years that the path forward for men is to neither devolve back into the buffoonish toxic hyper-masculinity currently platformed by the likes of Trump and Andrew Tate, and the “broligarchy” they all just elected — but also not to internalize the misandrous tendencies of the worst wing of woke-ism that paints all men as inherently bad/toxic/oppressive. Rather, the task for men is to honor their yin *and* their yang, to strive for a kind of “swashbuckling vulnerability,” to try to be a “mensch with an edge” who is both ballsy and respectful towards women. (I’m aiming to dig back into this project in 2025, so keep an eye out for excerpts coming your way next year.)

Tragic Optimism

Over the course of my creative career we’ve seen a strong through-line in the quixotic effort to turn my own deeply “felt oxymoronic-ness” into various pocket philosophies and paradoxical approaches. This track took its most full-blown form with I Want a Better Catastrophe, a “sprawling mess of a book” (one amazon reviewer) that “incisively and charmingly” (another amazon reviewer) brings a gallows-humor sensibility to the many paradoxes of the Climate Emergency, including:

We’re all in this together. NOT!

It’s too late AND it’s also never too late.

The Transition must be just AND fast.

Geoengineering is a terrible idea that we might have to do.

We have met the enemy and he is us. No, them! But also us. But mostly them.

Another end of the world is possible.

Etc.

Beyond all these contradictions that are structurally part of the climate emergency due to the injustice, asymmetry, collective-action-problem-ness and terrible timing inherent in the crisis, there is also the one that always comes up in our hearts when we face great challenges and attempt great things: the hopelessness of our situation and the hope — or at least courage — we must nonetheless bring to face it. This paradox is arguably the central exploration of Better Catastrophe. And central to that exploration is the philosophy of tragic optimism, developed by the great Austrian existential psychologist and death camp survivor Viktor Frankl.

Here’s how Frankl describes it in Man’s Search for Meaning (translated into 37 languages; 16 million copies sold):

Saying yes to life in spite of everything.

Here’s how Boyd describes it in I Want a Better Catastrophe (translated into 0.5 languages; 5,000 copies sold):

…Many homes across Canada have something called a “tickle-trunk.” A chest full of dress-up items: hats and capes and boas and fake mustaches and the like. These days, if you open my tickle-trunk (it’s the existential kind) and dig down past the hoodie of despair and the hopium-tinted glasses and the mustache of doom, you’ll find a cape of “tragic-optimism.” [...]

When I’m broken-hearted, but still want to attempt large things, I reach for my “cape of tragic-optimism.” I put it on and feel, well, broken-hearted — but now in a more soulful and empowered way. It will all end badly, I tell myself, but not quite as badly as it would if I did not act. So let me do something. While expecting nothing. While still longing for everything. And I call upon that grand longing — for everything wrong to be set right and everything broken to be set whole — to help me act in as large and open-hearted a way as I can, even in the face of inevitable failure. Putting on my cape, I feel a commitment to truth, beauty, solidarity, and, yes, strategic thinking.

We live in an era when the old world (fossil-fueled capitalism, gender binaries, pax Americana, et al.) is dying and the new world (fill in the blank, good and bad) is struggling to be born. It’s an “interregnum” — a time between kings, between world orders. Gramsci describes such a time as full of “morbid symptoms.” Zizek as “a time of monsters.” 350 co-founder Jamie Henn tells us, “Everything is coming together, as everything is falling apart.”

This is our world. Trump’s re-election and yet another failed climate COP are just the latest monsters and symptoms. We didn’t choose to live at this time, but here we are. And so we must find a way to be tragically optimistic about it. No easy task. According to Frankl, this requires us to lean hard into three of humanity’s noblest capacities: “(1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life's transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action.”

That’s quite a to-do list to pin to one’s fridge, but I’m trying. Yes, the world is awful, but then I remind myself: it’s also much better than it once was, and it can be much better than it is. Hope is a muscle; let’s work it. We also have a muscle for “being in uncertainties” and a muscle for “self-care” — we need to work those, too. There’s tools to help us “vent” our anger, frustration, even our despair, at the contradictions we face, even if they can’t be resolved. Let’s use them. And, yes, the world may break our hearts, but we can grow “strong in our broken places.” I know I’ve grown strong in some of mine over these decades. And I’m still growing, still learning; I’m still in process. In spite of my long career wrangling paradoxes, they sometimes still knock me on my ass. But as the poet said, then we get back up again.

So please stay tuned for more from me as I delve deeper into my own paradoxes and attempt to wrangle some of the monstrous ones running wild out there.

And whether it’s a cape of tragic-optimism or a pair of can-do pessimism goggles or a dark robe of skeptical mysticism or a waistcoat of “Negative capability” or a leather jacket of compassionate nihilism or a pink camo of enlightened machismo — or some strange pairing you yourself invent with the help of a Vent Diagram or an Eternal Debate — may you grab hold of your paradoxes and stay with the trouble.

Thank you, one again! Earlier today when I wrote my new year’s resolution list I included “read more from Andrew Boyd”…then this latest from you appeared in my inbox. Or rather, I conjured it and pulled it out of my “existential tickle-trunk” ;) So rich in tools and references. I’m looking forward to jumping off into some of those links. Grateful Canadian neighbour here :)

Wonderful Andrew, thanks, I especially like the tools at the end and the vent diagrams.